We inaugurate our first EM debt travel report with a trip to Washington, DC, where the fall meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) were held from October 10 to 16.

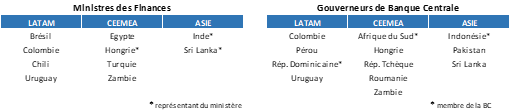

We spent three days meeting with policymakers, IMF country analysts, political analysts, and think tank experts. We had the opportunity to meet with finance ministers (Colombia, Chile, Hungary, Turkey, Zambia) and central bank governors (Colombia, Peru, Dominican Republic, South Africa, Hungary, Zambia, Indonesia) from emerging countries across all regions (see table below for details of countries attending). We were also able to share info with many EM bond investors (about 300 attended). The overall sentiment was negative, undermined by uncertainties regarding global monetary tightening, geopolitical, economic and financial risks. Recent events have highlighted the difficulties faced by many developing countries, mainly low-income ones such as Tchad, Sri Lanka, or Pakistan, but also some middle-income countries such as Tunisia. The significant appreciation of the dollar YTD, in reaction to the massive tightening of US monetary policy, has been affecting governments whose debt is mainly denominated in USD. This vicious circle is being transmitted through 1) the currency channel, with the depreciation of local emerging currencies increasing the cost of servicing debt, and 2) the interest rate channel, with tighter domestic financial conditions depressing domestic activity and the tighter external conditions closing access to international capital markets. In this context, many developing countries are likely to turn to multilateral financing sources, with a willingness to prioritize “sustainable” financing (cf. the new IMF’s Resiliency and Sustainability Trust and the new World Bank’s Scaling Climate Action by Lowering Emissions (SCALE) fund).

We spent three days meeting with policymakers, IMF country analysts, political analysts, and think tank experts. We had the opportunity to meet with finance ministers (Colombia, Chile, Hungary, Turkey, Zambia) and central bank governors (Colombia, Peru, Dominican Republic, South Africa, Hungary, Zambia, Indonesia) from emerging countries across all regions (see table below for details of countries attending). We were also able to share info with many EM bond investors (about 300 attended). The overall sentiment was negative, undermined by uncertainties regarding global monetary tightening, geopolitical, economic and financial risks. Recent events have highlighted the difficulties faced by many developing countries, mainly low-income ones such as Tchad, Sri Lanka, or Pakistan, but also some middle-income countries such as Tunisia. The significant appreciation of the dollar YTD, in reaction to the massive tightening of US monetary policy, has been affecting governments whose debt is mainly denominated in USD. This vicious circle is being transmitted through 1) the currency channel, with the depreciation of local emerging currencies increasing the cost of servicing debt, and 2) the interest rate channel, with tighter domestic financial conditions depressing domestic activity and the tighter external conditions closing access to international capital markets. In this context, many developing countries are likely to turn to multilateral financing sources, with a willingness to prioritize “sustainable” financing (cf. the new IMF’s Resiliency and Sustainability Trust and the new World Bank’s Scaling Climate Action by Lowering Emissions (SCALE) fund).  This adverse environment is affecting emerging economies to varying degrees. While some defaults have already been recorded (Zambia, Sri Lanka, Surinam, Ethiopia) and some appear to be done deals regarding market valuation (Ghana, Pakistan, Argentina, Ecuador, El Salvador, etc.), the emerging universe has globally reduced its vulnerabilities to external conditions. 120 emerging and developing countries have cumulative maturities of about $1.5 Trn over the next 4 years. Half of this is owed by 12 investment-grade emerging countries representing $750bn of bonds. 38 middle and low-income countries with low debt ratios have maturities of $250bn. For these 50 countries, debt sustainability is not an issue. Restructuring is an issue for the remaining 70 low-income countries, 35 of which have weak economies but low debt level and interest costs, while the other 35 are close to or already in financial distress. The debt of these 70 countries, all of which are eligible for the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), represents the remaining $500bn. These countries rarely have access to international bond markets, as their debts have historically been contracted with bilateral (countries) and multilateral (IMF, WB, etc.) creditors. Their representation in emerging bond indices is marginal, limiting systemic risk. The Common Framework (CF), a mechanism designed by the G20 during the pandemic, aims at involving official bilateral creditors that are not members of the Paris Club, mainly China, in the debt relief process for countries in financial difficulties. However, this mechanism is not effective (agreement on general principles) and losescredibility as time goes by. To alleviate the financial burden of highly indebted countries, new tools will have to be put in place, guaranteeing the comparability of treatment of different creditors through effective enforcement mechanisms. One proposal is a Most Favored Creditor contractual agreement with terms that would also apply to bondholders.

This adverse environment is affecting emerging economies to varying degrees. While some defaults have already been recorded (Zambia, Sri Lanka, Surinam, Ethiopia) and some appear to be done deals regarding market valuation (Ghana, Pakistan, Argentina, Ecuador, El Salvador, etc.), the emerging universe has globally reduced its vulnerabilities to external conditions. 120 emerging and developing countries have cumulative maturities of about $1.5 Trn over the next 4 years. Half of this is owed by 12 investment-grade emerging countries representing $750bn of bonds. 38 middle and low-income countries with low debt ratios have maturities of $250bn. For these 50 countries, debt sustainability is not an issue. Restructuring is an issue for the remaining 70 low-income countries, 35 of which have weak economies but low debt level and interest costs, while the other 35 are close to or already in financial distress. The debt of these 70 countries, all of which are eligible for the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), represents the remaining $500bn. These countries rarely have access to international bond markets, as their debts have historically been contracted with bilateral (countries) and multilateral (IMF, WB, etc.) creditors. Their representation in emerging bond indices is marginal, limiting systemic risk. The Common Framework (CF), a mechanism designed by the G20 during the pandemic, aims at involving official bilateral creditors that are not members of the Paris Club, mainly China, in the debt relief process for countries in financial difficulties. However, this mechanism is not effective (agreement on general principles) and losescredibility as time goes by. To alleviate the financial burden of highly indebted countries, new tools will have to be put in place, guaranteeing the comparability of treatment of different creditors through effective enforcement mechanisms. One proposal is a Most Favored Creditor contractual agreement with terms that would also apply to bondholders.

Regional focus: Latin America – central bank credibility in the face of political risk

A shift to the left of the political spectrum has taken place in the South American region since the pandemic. The latest example to date was the victory of Gustavo Petro in the second round of the Colombian presidential election on June 19. A former member of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (FARC), he was elected on a platform promoting social and environmental justice. A scenario that echoes the latest presidential elections in Peru and Chile: high social expectations and fears of budgetary slippage with a risk of foreign capital outflows. In this context, the role of central bankers is essential in maintaining a coherent policy mix. In this respect, Julio V elarde and Leonardo Villar, respectively governors of the central banks of Peru and Chile, whom we met in Washington, are

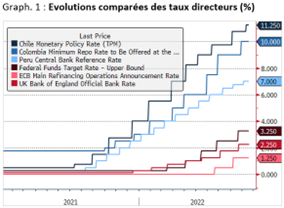

elarde and Leonardo Villar, respectively governors of the central banks of Peru and Chile, whom we met in Washington, are determined to continue to act to make inflation rates converge toward their inflation targets. They are taking on the unpopular role of ensuring that their countries’ prices and currency stay anchored, ultimately ensuring global investors’ confidence. Following the example of Chile, this has been reflected since Q3 2021 by monetary policies having reacted swiftly to rising inflation rates. Cumulative increases in policy rates of 675bp, 825bp, and 1075bp (see graph 1) have enabled the Peruvian, Colombian, and Chilean economies respectively to present real rates currently close to -2%, well above the real rates in force in the developed world (see graph 2).

determined to continue to act to make inflation rates converge toward their inflation targets. They are taking on the unpopular role of ensuring that their countries’ prices and currency stay anchored, ultimately ensuring global investors’ confidence. Following the example of Chile, this has been reflected since Q3 2021 by monetary policies having reacted swiftly to rising inflation rates. Cumulative increases in policy rates of 675bp, 825bp, and 1075bp (see graph 1) have enabled the Peruvian, Colombian, and Chilean economies respectively to present real rates currently close to -2%, well above the real rates in force in the developed world (see graph 2).

The separation of executive and legislative powers also acts as an institutional safeguard, with all three governments lacking the minimum majorities to implement extreme reformist policy agendas. In addition, Mauricio Marcel and Jose Ocampo, the Finance ministers of Chile and Colombia respectively, whom we also met, were appointed in part to reassure the international financial community. With classical Anglo-Saxon backgrounds and reputations of solid qualification, the main task in their respective governments is to try to reconcile high social expectations with sustainable fiscal policies. In sum, monetary and fiscal institutions have gained credibility: better institutional frameworks, clear rules and laws governing them, and professional staff. This has been seen in the early action of central banks in the current global monetary tightening. Country investment cases that in some ways recalls the Mexican case during the election of Andres Manuel Lopes Obrador in 2018. The incumbent president had then widely worried the financial community based on a program deemed too leftist and potentially expensive, before subsequently proving to be a fiscal conservatism hard-liner.

Country focus: Dominican Republic (Presidential Republic of 10.7M inhabitants, GDP of $184bn)

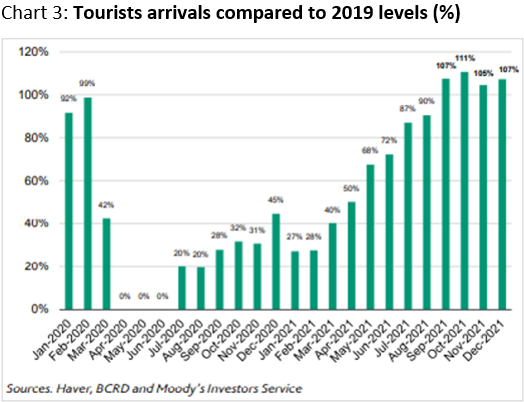

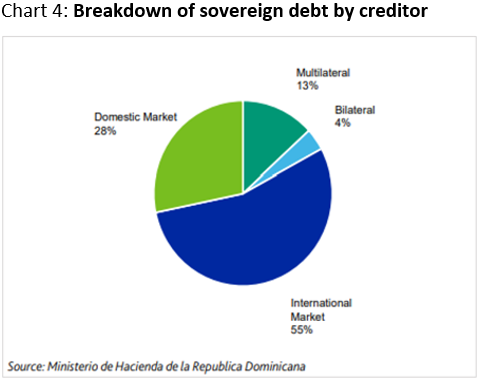

Messages from government officials and the IMF have been very constructive. GDP growth is decelerating very gradually, converging towards its medium-term trend (5% yoy). Growth is largely driven by investments in infrastructure and manufacturing, while tourism has been booming since early 2021 (see chart 3). The economy is more diversified and less dependent on tourism than other Caribbean economies. Remittances from abroad are now expected to reach nearly $9bn per year. Inflation is gradually converging to the central bank’s target of 3% to 5%. The government expects it to be within the target range by mid-2023. The appreciation of the Dominican currency (DOP, +7.5% ytd), thanks to higher interest rates, robust tourism, remittances, and foreign direct investments (FDI) flows, has helped contain inflationary pressures (8.6% yoy as of 09/30). The central bank adopted a restrictive monetary policy stance via a higher target policy rate (+525bp at 8.25%) and the absorption of liquidity through medium-term notes. However, credit growth remains slightly higher than nominal GDP growth. The central bank estimates that 2% is the neutral level of the real interest rate. The revised fiscal deficit target for this year is 3.6% of GDP, but the government is likely to fall short of this level. The authorities could use the additional resources to pre-finance 2023 spending. The estimate of the damages caused by hurricane Fiona could climb up to DOP25bn, but the financial cost will be absorbed by existing resources. The Minister of Finance has indicated that there is no urgency to issue new short-term debt, as the government has DOP190bn in cash. The authorities are analyzing the implementation of a fiscal rule with the IMF technical assistance, but this plan is not expected to occur before the next elections (2024). Debt denominated in foreign currency (USD) has been reduced in favor of local currency financing but remains by far the largest source of financing (see chart 4). The financing needs for 2022 were fully met at the beginning of the year. The financing seasonality of bond issuance usually takes place in January/February and November/December. The appreciation of the currency has largely contributed to the reduction of debt to GDP (58% expected in ’22 vs. 71% at the end of ’20). No sudden adjustment of the exchange rate is expected, but rather a very gradual depreciation as flows are likely to continue being supportive. Since the pandemic, the government has been committed to maintaining the country’s financial rating in the BB category. The country’s political stability is reflected in the premium paid by investors.

Messages from government officials and the IMF have been very constructive. GDP growth is decelerating very gradually, converging towards its medium-term trend (5% yoy). Growth is largely driven by investments in infrastructure and manufacturing, while tourism has been booming since early 2021 (see chart 3). The economy is more diversified and less dependent on tourism than other Caribbean economies. Remittances from abroad are now expected to reach nearly $9bn per year. Inflation is gradually converging to the central bank’s target of 3% to 5%. The government expects it to be within the target range by mid-2023. The appreciation of the Dominican currency (DOP, +7.5% ytd), thanks to higher interest rates, robust tourism, remittances, and foreign direct investments (FDI) flows, has helped contain inflationary pressures (8.6% yoy as of 09/30). The central bank adopted a restrictive monetary policy stance via a higher target policy rate (+525bp at 8.25%) and the absorption of liquidity through medium-term notes. However, credit growth remains slightly higher than nominal GDP growth. The central bank estimates that 2% is the neutral level of the real interest rate. The revised fiscal deficit target for this year is 3.6% of GDP, but the government is likely to fall short of this level. The authorities could use the additional resources to pre-finance 2023 spending. The estimate of the damages caused by hurricane Fiona could climb up to DOP25bn, but the financial cost will be absorbed by existing resources. The Minister of Finance has indicated that there is no urgency to issue new short-term debt, as the government has DOP190bn in cash. The authorities are analyzing the implementation of a fiscal rule with the IMF technical assistance, but this plan is not expected to occur before the next elections (2024). Debt denominated in foreign currency (USD) has been reduced in favor of local currency financing but remains by far the largest source of financing (see chart 4). The financing needs for 2022 were fully met at the beginning of the year. The financing seasonality of bond issuance usually takes place in January/February and November/December. The appreciation of the currency has largely contributed to the reduction of debt to GDP (58% expected in ’22 vs. 71% at the end of ’20). No sudden adjustment of the exchange rate is expected, but rather a very gradual depreciation as flows are likely to continue being supportive. Since the pandemic, the government has been committed to maintaining the country’s financial rating in the BB category. The country’s political stability is reflected in the premium paid by investors.